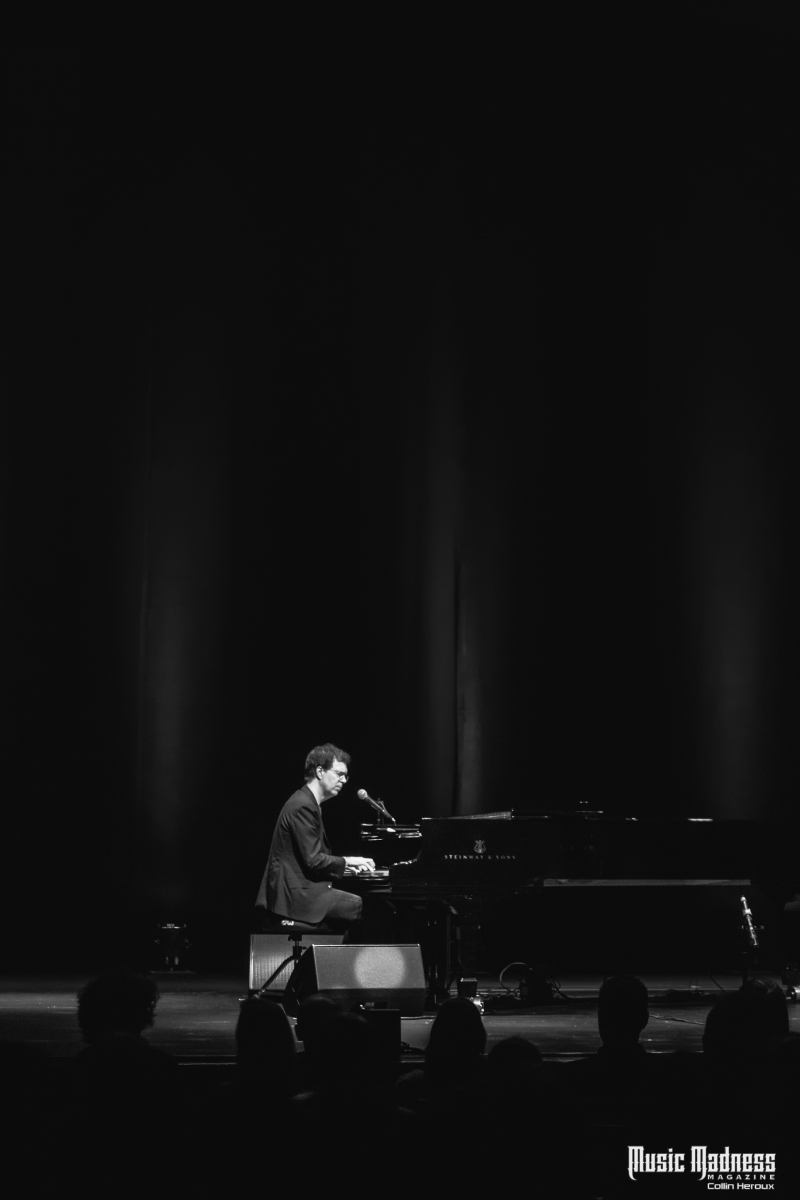

It takes a special kind of ability to captivate an entire room playing just a piano. The recipe of one person, three stories’ worth of audience, and a grand piano would likely be the stuff of nightmares for most anyone – even some pianists, I’d wager – simply because of the sheer ratio of viewers to performer, the notion that any errant note will resound throughout the room for all to hear. But this is the milieu in which Ben Folds has existed for ages, as comfortable and capable as the leader of Ben Folds Five or in concert with collaborators like yMusic, as he is with nearly 1500 people gathered to watch him play his Steinway alone on stage. This stop at the Emerson Colonial Theatre is part of his In Actual Person Live for Real Tour, so named for obvious reasons. Like many artists touring these days, Folds has no new album to promote but instead is participating in the suddenly-grand tradition of taking to the road simply because one finally can, and he’s already announced dates in 2023 where he’ll be performing with local orchestras in a handful of cities. And in a setlist that encompasses his career as both a solo artist and Ben Folds Five, he’s compiled a showcase for his talent of writing concise character studies and introspective passages, moving or funny and often both at once.

The grand piano is a master’s instrument, an impressive apparatus, all those keys capable of building out an entire song from the lowest register to the highest – provided one can do so many things at once. Seeing him live, it becomes immediately apparent how Folds morphed the status of the piano in rock music over the past thirty years: he’s thrilling to see play, ruling the entire room with muscle memory of just how forceful or delicate to tap a dozen keys in each-half second. The grand’s sound is true to its name, generating a certain primal resonance that can easily get a crowd going. And that he does amply throughout the night, thriving off the energy being returned from the seats. The crowd provides clapped percussion during the intro of ‘Annie Waits’, sings the intro to ‘Effington’, and the collective voice of the room is, unexpectedly, a suitable stand-in for Regina Spektor on ‘You Don’t Know Me’. That last one is just a single example of an exhaustive list of collaborators Folds has worked with through the years, including understandable names like Sara Bareilles and Amanda Palmer, as well as some unexpected guests like William Shatner, who featured on an album released in 1998 by Folds’ one-off side project Fear of Pop.

Alongside ‘Annie Waits’, Folds opens the night with a few selections from his most recent LP, So There, his collaboration with yMusic. He starts with the title track and then moves on shortly thereafter to ‘Capable of Anything’, an inversion of the usual sentiment of the phrase. Speaking before the song, Folds says he never used to believe people when they’d say it, but in the final lyric he ponders: “you don’t seem to think that you could… steal, or cheat, or kill, or lie – but you might”. We’re capable of more than we think, but often in the way that we’d best stop ourselves from exploring.

Throughout the evening, one of the most stunning aspects of the performance is just how precise Folds is at the keys – it’s hardly a surprise, but nonetheless a marvel. In ‘Evaporated’ he moves his left hand over his right to play higher notes; and during faster, louder songs when he slams the keys with his fist, elbow, or a single knuckle, even that cacophony comes out feeling cohesive. This tendency does prove to complicate things later in the night though, where Folds notes that the piano might be in need of repair soon, though the exact problem is not readily audible in the theatre, and the audience gets a little jazzy improv performance entitled ‘The Piano is Shitting the Bed’ – or so one would assume, given that those are just about the only lyrics in the song. There are a few of these unplanned moments throughout the night, including how his recounting of contributing to the soundtrack for the film Me, Myself, and Irene leads to him performing a snippet of Steely Dan’s ‘Barrytown’. He also details the origin of Rockin’ the Suburbs favorite ‘Zak and Sara’, the words to which he claims once prompted his producer to ask in the studio, “Are you sure those are the lyrics?” It turns out that the song is a combination of a recurring music-store scene, Jim Morrisson predicting the existence of techno offhandedly in an interview, and one or two other equally disparate influences.

The audience even recreates a now-famous bit from Folds’ first live album: from high up in the theatre what sounds like a group of three or four people have waited well into the evening to shout in unison, “Rock this bitch!” Another of Folds’ improvised ditties, he recreates it (sort of) not on the piano, but by slapping the microphone with an open hand and a maraca. Genial and vaguely professorial-looking with his glasses, blazer, and sneakers, Folds has always had a keen sense for how to deploy profanity in his music, one of the shining examples of this being the title track of Rockin’ the Suburbs, where the impotent protagonist attempts to “warn” the audience that he’s “gonna say ‘fuck’”. Satire aside though, some people would have clearly appreciated such a warning, as during the hand-wringing days of the Bush administration his use of profanity was a pain point for some who’d see him open for other acts such as John Mayer.

As the final song of the night, Folds chooses ‘Army’, and this one finds the audience harmonizing in groups, stratified by seating as if they were all industry plants. As he points to each third of the room, Folds nods with approval and a bit of surprise. The crowd gives him a standing ovation as he departs, but he returns once more, evidently confident that the piano can survive one final ballad, ‘The Luckiest’. While Folds’ songs are so often sarcastic and clever, or occasionally somber and unflinching, the sincerity of this song makes it a standout. It perfectly captures the feelings known well to those in love, the grateful questioning of how you ever got by without seeing the face of the person who has become so integral to your experience of life. Its position in the setlist at the very end of the show, and its uniqueness in his catalog, make it an apt parting gift from the artist, ending a far-ranging performance – both temporally and tonally – with a moment of absolute candor.

Review and photos by Collin Heroux