“Little known fact… We actually did put out a record last summer.” These are the words of Bright Eyes frontman Conor Oberst, joking from the edge of the stage at Connecticut’s Westville Music Bowl on a warm summer evening. Everybody in attendance knows, of course, that Oberst and company are here touring in support of their latest record, Down in the Weeds, Where the World Once Was – but the shocking bit is that the album is already nigh on a year old. Time has had a way of compressing itself over the past year and a half, with no delineation between days spent predominately inside and solitary.

But in solitude is where this author would wager the music of Bright Eyes finds people the most – perhaps not in the pandemic-induced kind, but solitude nonetheless. Oberst remarks later that “We don’t have a lot of happy songs,” and it’s true; from the very beginning Bright Eyes have always looked sadness square in the eye, sparse arrangements hoisting heartbroken lyrics on songs like ‘A Perfect Sonnet’ more than two decades ago, through to now where they find more orchestral accompaniment. Oberst’s voice possesses a wavering quality even in its strongest moments as if channeling some deep pain. But as with all music that looks grief and despair in the face, there’s an unparalleled sense of community derived on the far side of that woe, a community seen in all the faces of the audience.

This is only the band’s second show since going on hiatus in 2011 after touring in support of The People’s Key – but ardent fans of folk-indebted indie rock know that Oberst in particular has been anything but dormant in that time. He’s released a trio of solo records, as well as an extremely high-profile collaboration with Phoebe Bridgers under the name Better Oblivion Community Center. It was only a matter of time before the prolific Oberst gathered his collaborators Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott to circle back to Bright Eyes.

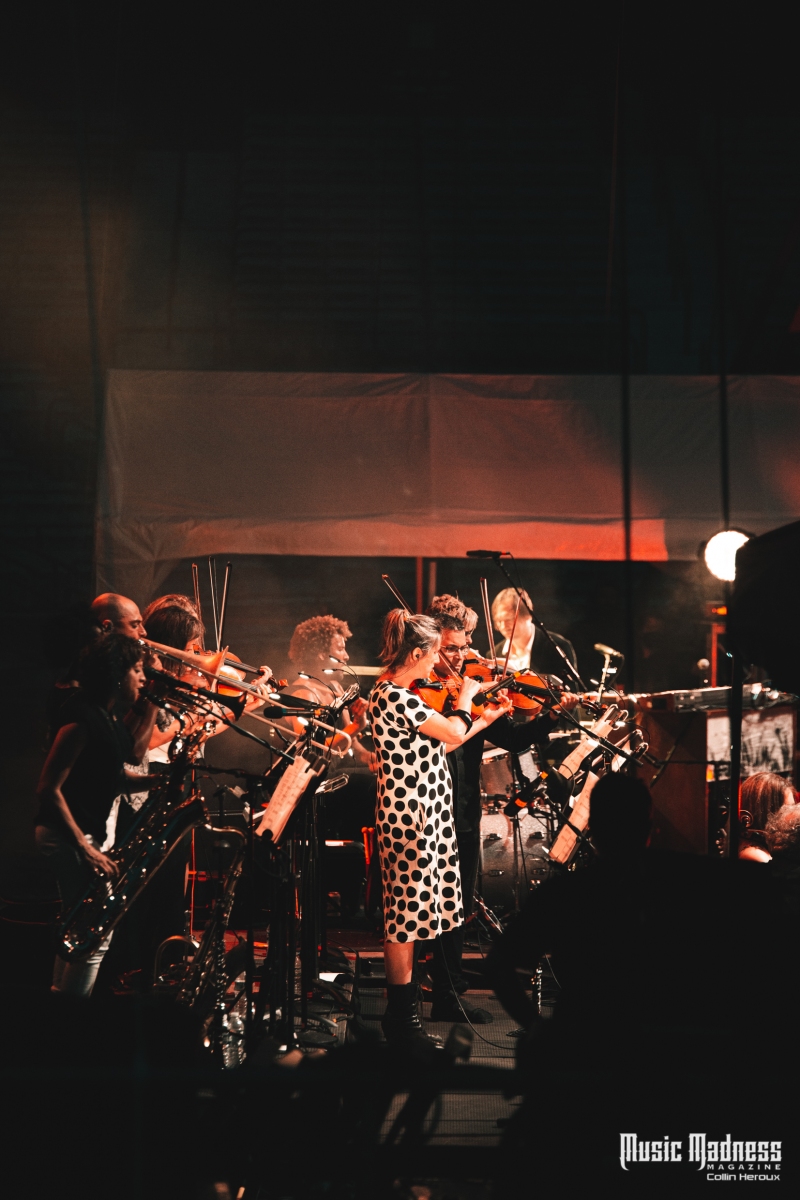

For the band’s resurgence – as well as that of live music as a concept – they’ve opted for scale, arriving as a six-piece as well as recruiting a cadre of woodwind, horn, and string players to back them up. Down in the Weeds… is absolutely lush with these intricate arrangements, a sonic world that the core trio of Bright Eyes has built to cradle most of the album – though it does feature some notable departures from the bombast, including ‘Pan and Broom’, which quietly assembles its verses of upwardly-inflected phrases and questions over a minimal drum machine. But live, even the most sparing of tracks from the record gains punch, as drummer Jon Theodore supersedes the programming in that song’s final minute with some exciting double-time percussion.

The same goes for a song like ‘Neely O’Hara’, which during a lull in the set Oberst introduces as a song he wrote when he was just eighteen. Originally the song is low-key, guided by a reversed tape loop, creating an atmosphere of hazy distortion; but played in person the string section soars, creating a whole new life inside the song, the massive collection of samples that close the record version replaced by a stunning guitar solo that calls out into the night. Oberst’s discography has undoubtedly grown, morphed, and changed, living a life of its own alongside him with Mogis and Walcott arranging tracks both old and new for maximum effect.

Elsewhere in the night, the band plays ‘One and Done’, a song about Oberst’s late brother. It’s a song with few specifics, but late in the verse when Oberst sings, “There’s no denying it / this little box fits everything there is,” the sadness is palpable in his voice as he utters a declaration of such finality. Throughout the show, Bright Eyes revisit nearly all of their albums, chronicling the deeply internal (‘Poison Oak’) to the worldwide and catastrophic (‘No One Would Riot for Less’). When Oberst sings songs sans guitar, he keeps his arms and the mic close to his chest like a boxer in a defensive pose, until the emotional climax of songs where his limbs will reach rapidly to the sky. Other times he’ll kneel on the lip of the stage and extend a hand in the audience’s direction, reaching out literally and figuratively in a way we’ve all forgotten how.

But amid these scenes pulled from nearly a quarter-century of music-making, in the tracks from Weeds there is a glimmer of something that shines brighter than before: a clarity, a wisdom, a shifted sense of perspective in the lyrics that no doubt has solidified in the last ten years. On songs like ‘Forced Convalescence’, Oberst ruminates on turning forty, seemingly more at peace with the inescapable mundanity and mortality that underpins life. When he claims his medication is “fighting [his] fantasies,” it’s not clear if those are positive or negative, as the term is applied to both in a clinical setting. But in the chorus-backed conclusion of the song, he declares, upon seeing everything, that he is “overcome with love”.

The final track of the main set is ‘Comet Song’, which also closes the new record. Awash in memories, the sense of finality from earlier creeping in again thematically, it concludes with the thought of a newborn baby, blissfully unaware of the way in which life mimics the brilliant disintegration of a comet: “You’re approaching even as you disappear,” howls Oberst as the strings overtake everything. He grabs a bouquet of white flowers from his piano and tosses them out to the audience, and for a short while the stage falls quiet. That final line isn’t quite a comforting sentiment, but there is an element of hope in it, a kind of Sisyphean embrace of the absurd reality that we all share.

Before bidding farewell, the band returns as a three-piece to play one of Bright Eyes’ most iconic songs, ‘First Day of My Life’. The song speaks of “blankets on the beach”, and while the floor of the stadium is AstroTurf some people have indeed brought picnic blankets, lying there listening to a song which for 16 years has held an unchallenged monopoly on perfectly conveying the way in which true love is a rebirth, a transformative deluge of infinite possibility. A soft light bathes the audience as they sing along, and all-around people turn to the ones who make them feel the way the song describes. The sense of peace at that moment feels like a minor miracle.

Bright Eyes’ final missive is ‘Easy/Lucky/Free’, the last cut from 2005’s Digital Ash in a Digital Urn. Though written many years prior, it complements the themes of ‘Comet Song’ perfectly, confronting death and the oft-uncaring world with acceptance. Despite such a span of time between them, both the main set and encore end with songs that encapsulate the essence of Oberst’s lyricism with Bright Eyes. There’s a thread of pain and loss strung all through the band’s work, as he has dissected his own experiences and the world in song. But with Down in the Weeds Where the World Once Was, the band and Oberst himself offer a look at an evolution of that perspective, not immune to the hardships of life, but, with the benefit of time, a bit more aware of how to face them.

Check out the band at BRIGHT EYES