There’s a crowd of young people sprinting through a park, running west into a golden hour gilded enough to make the Providence skyline look pretty, even as it’s beset on the western side by looming storm clouds. They’re kicking up dust as they all run for the rail, from which they’ll dare not move for the next four hours in order to remain in the front row. Some have been there since 8 am, apparently, and as they arrive at the barrier they throw their arms wide to reserve space for friends who are still running, staggered a bit by the metal detectors. It’s the type of dedication that, while certainly born from the sincerest of places, might inspire mixed feelings in the evening’s mononymous headlining act, Mitski.

When Mitski razed her online presence in the wake of her 2019 opus Be the Cowboy, it was unclear for a time if she would ever make music or perform live again. And while that album and its wild success brought her levels of recognition such that she felt the need to depart the public eye, even before then the seeds of this departure had been sown. ‘Geyser’, the first song from that album, states about her career that she “hear[s] the harmony only when it’s harming me”. Mitski’s music has long confronted the difficult reality of making one’s way in the world, like how on Puberty 2 she says, “I wanna see the whole world / I don’t know how I’m gonna pay rent”; and while those issues are likely in the past for a musician touring the globe, new wrinkles have risen in their place.

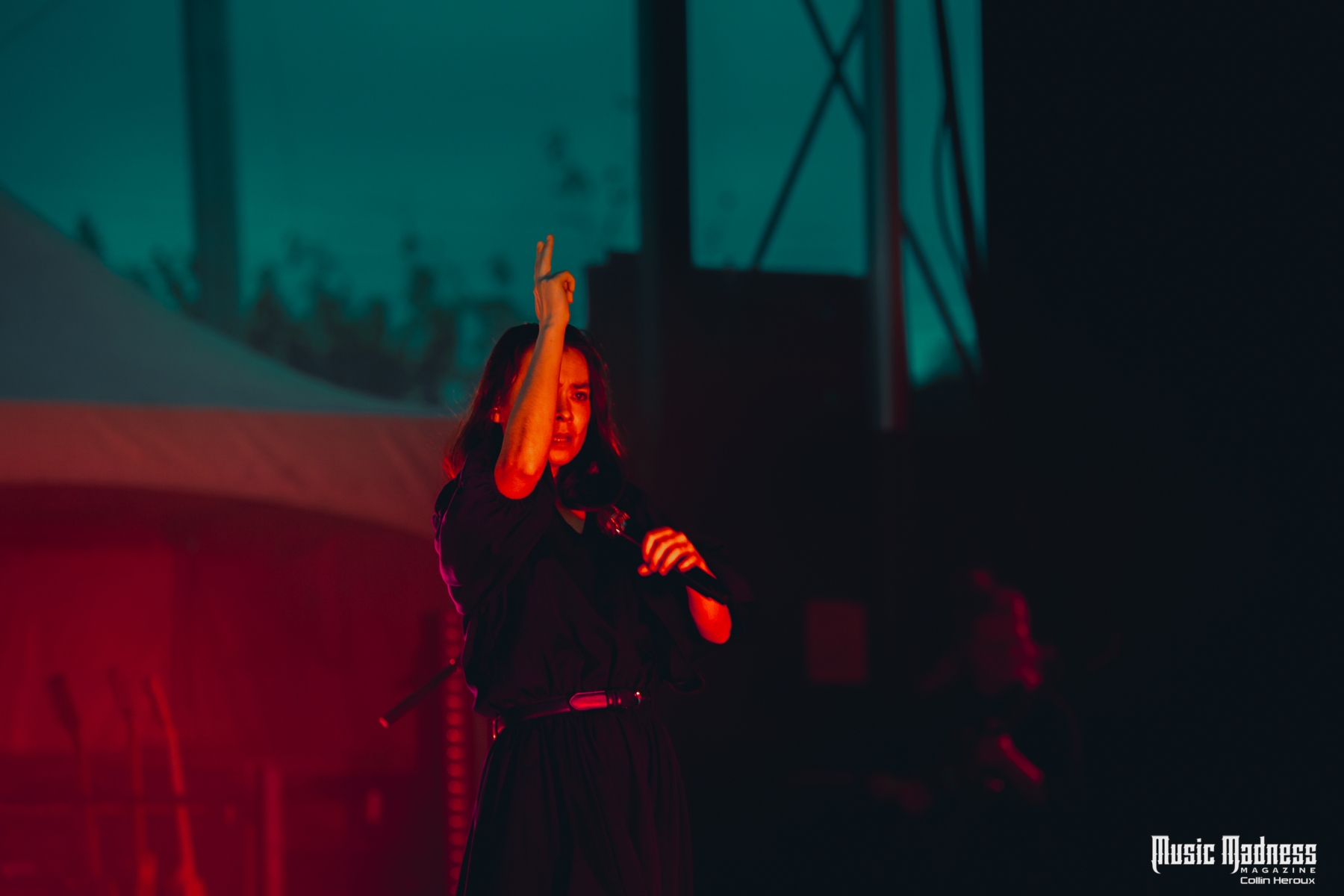

By the time Mitski is scheduled to take the stage, the clouds from the west have come to envelop all of Providence, though in a benevolent act of nature there’s a conspicuous spot left slightly brighter over the park on the city’s eastern side. And in that little eye, Mitski and her band climb the metal staircase and set up to perform. Much of center stage is left open, with the instrumentalists arranged roughly in a half-circle behind her. Since she started performing songs from Be the Cowboy live around 2018, Mitski has elected to not play instruments herself, instead crafting elaborate choreographic routines that elevate the performance and often see her whirling around or tossing herself to the floor of the stage.

She begins with the rapidly-ascending ‘Love Me More’, taken from her latest record, Laurel Hell. Mitski’s songs, no matter the speed, always carry a piercing intensity, and while ‘Love Me More’ sounds like a shining 80s ballad, inherently danceable, it pleas find Mitski desperately hoping that love can fix everything, even the weariness she feels when she ponders the future. It’s a pristinely-produced panic attack, driven by the fear that the buffer between her and her dread is waning.

‘Working for the Knife’ – the single that announced to the world Mitski was returning from her hiatus – once again opens up about the complex nature of her relationship to her work, starting with a younger version of herself wishing to be making things, but finding the reality of doing it simultaneously demotivating but inescapable. Making music under her own first name, she in essence has to be a product to put her ideas out into the world, and it’s not something that sits well with her – after the final titular refrain, where she admits she is in fact “dying for the knife,” she takes hold of her wireless microphone by the top and drags it across her neck like a blade while the instruments soar behind her. The knife is a threat, something that creates a need – it’s not only the need to literally work for money, it’s the desperate desire to create; and then it’s also the audience, the danger of being opened up and dissected by observers.

Making albums for ten years, she has grown up in songs that directly chart her aging: in ‘First Love/Late Spring’ she recalls trying to seem more mature only to discover that at the age she was trying to act she would feel not like an adult but a “tall child”, beholden to emotional whims and feeling like she’d do anything, even toss herself off a bridge, for someone she’s fallen for. It’s a universal sentiment, growing old and realizing that the people your childhood self looked to probably had no idea what they were doing most of the time, their age concealing a turbulent inner world of emotion that no child can imagine someone so much older possessing. With this audience, mostly young and mostly non-men, it’s ample evidence that Mitski’s music continues to reach and resonate deeply with people who are primed to feel the most connected to it.

When she arrives at ‘Geyser’ in the setlist, she carries her mic across the stage as one would a heavy burden, Christlike, exemplary of how her chosen career has so often felt. She holds her arms out by the end, pleading again, knowing that she’s inexorably intertwined with this idea even at the cost of other things. As she said in ‘Because Dreaming Costs Money, My Dear’: “play your violin / I know it’s what you live for”. Even as she knows what she’s given up to pursue it, this act of creation and musicianship is too vital to abandon.

Night descends completely just in time for ‘Drunk Walk Home’ – after she flings herself to the floor during the opening, the entire crowd roars with her at the line, “Fuck you and your money!” It sits like a companion piece to ‘Townie’, another track from Bury Me at Makeout Creek, where Mitski is surrounded by male arrogance and obliviousness. In its decidedly-heavy outro, her choreography becomes pugilistic, walking rigidly back and forth across the stage, arms striking out at the air in front of her. By the end, she has once again knelt on the stage. Some artists move as if the music is controlling them, some don’t move at all—Mitski moves like she’s in a battle, a bout she’s reliving each time she walks the lyrical path through each song, taming all of these sentiments once again. She confronts similar themes in ‘Your Best American Girl’, recounting a clash of her upbringing with her Japanese mother against her experience of America as a young person, and realizing with time that for all its differences and difficulties, her mother was imparting something important.

As equally stunning as her choreography is the brevity with which Mitski often writes. Over the course of the set, one realizes how in the past 10 years she has authored so many lyrical passages that are deeply emotionally taxing, but nearly all of them exist in songs less than three minutes in length; it doesn’t take long for them to exact their toll. One of these is ‘The Only Heartbreaker’, a study of a relationship where she resigns herself to the role of the villain in a relationship, though perhaps only because the other person’s passivity makes them seemingly immune to error. During the song she wraps one hand around her opposite wrist like she’s trying to restrain it, much like the titular character of Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove does with his “alien hand”, worried what it might do.

There’s an uncharacteristic pause after this song, long enough for the crowd to begin chanting her name. She resumes in a few moments with another run of songs, including older favorites like ‘Francis Forever’ and ‘Happy’. Then the gentle synth pulse of ‘Two Slow Dancers’ starts to ring out, signaling the closure of the main set. It’s a kind of generalized flash-forward, two people lingering in a moment of nostalgia, time having worn their features, wringing the last bit from something that could never last and in fact ceased long ago. “To think that we could stay the same,” Mitski calls out as the song reaches its crescendo and phone flashlights rise where lighters once would have been. Like so much of her work, the song is positively gorgeous but emotionally crushing.

Turning and considering going backstage for an encore break, Mitski decides against it. “I was about to walk offstage… but you’d be able to see us back there. We’re not gonna play pretend; this is the encore”. The final song of the night is ‘A Pearl’ – that shiny bauble is a fixation on the narrator’s mind, a product of turmoil that has left her unable to accept kindness or calm, and that inability creates distance that goes on to cause its own kind of trouble. When an oyster makes a pearl, it comes from the same material that forms its hard outer shell. The cycle outlined here hits home for those who have been so thoroughly surrounded by chaos that they lose the ability to really ever feel safe. Her elongation of the words in the final chorus along with the wailing guitar sums up all the frustration of finding oneself in that emotional double-bind.

At its conclusion after nearly two dozen songs, Mitski addresses the crowd a final time. “This has been a dream come true, thank you so much.” Whatever her rationale for returning to performing, and no matter what plans she has for the future in that regard, with Laurel Hell, as with the rest of her catalog, Mitski has crafted a beautifully-moving performance and songs that give voice to the difficulties of needing most the very things that can make you the most vulnerable: relationships, the experience of age, and creating art itself.

Review and photos by Collin Heroux