“Is there anything she can’t do?” This is the question MUNA vocalist Katie Gavin poses to the audience after Phoebe Bridgers joins them to perform their latest single, the impeccably crafted LGBTQ-forward pop anthem ‘Silk Chiffon’. Bridgers recently founded her own record label, Saddest Factory, with MUNA as one of the earliest signees – in addition to contributing vocals and a starring role in the music video for ‘Silk Chiffon’. A natural collaborator as well as a singular talent, she’s quickly become one of the most widely-known names in music following the success of her stellar LPs, Stranger in the Alps, and, most recently, Punisher.

After topping nearly every year-end list in 2020, fans of Bridgers were profoundly eager to see her perform the album, and she effortlessly sold out two nights at Boston’s gigantic Leader Bank Pavilion. Under that white seaside tent, there truly was a sense of mass communion, a return to something, and while Bridgers sarcastically branded the jaunt a “Reunion Tour”, complete with the desperate-80s-hair-band font on posters, underneath that irreverence there’s a wink of deep truth, a relief to be getting back to massive spaces like this to sing sad songs along with your friends. Bridgers’ music joins a long canon that brings people together by exploring vignettes that are often both deeply morose and deeply personal. This sense of somber embrace is found in the music of the late Elliott Smith, whom the album references heavily; it also recalls the folk-influence of Bridgers collaborator Conor Oberst’s work in Bright Eyes, and the baroque depression of bands like The National. There are endless endpoints to grab onto with Bridgers’ music, something for everyone to find in the nooks and crannies of its lyrics.

The narrative structures of these slices of life play not only an auditory role throughout the night, but a visual one, too – for each song from Punisher the towering projection screen behind Bridgers shows a different animated pop-up page of the same book, opening and closing to different scenes. It’s a fitting metaphor, as many of the songs here deal with pain from childhood. After playing ‘Motion Sickness’ from Stranger, Bridgers turns her back to the crowd and lingers underneath the book for the first time, PUNISHER emblazoned on its virtual cover. It cracks open to a scenic garden with a curved bridge as she launches into ‘Garden Song’, the first full-length track from the album, a shape-shifting myriad dreamscape that sets the tone for the night.

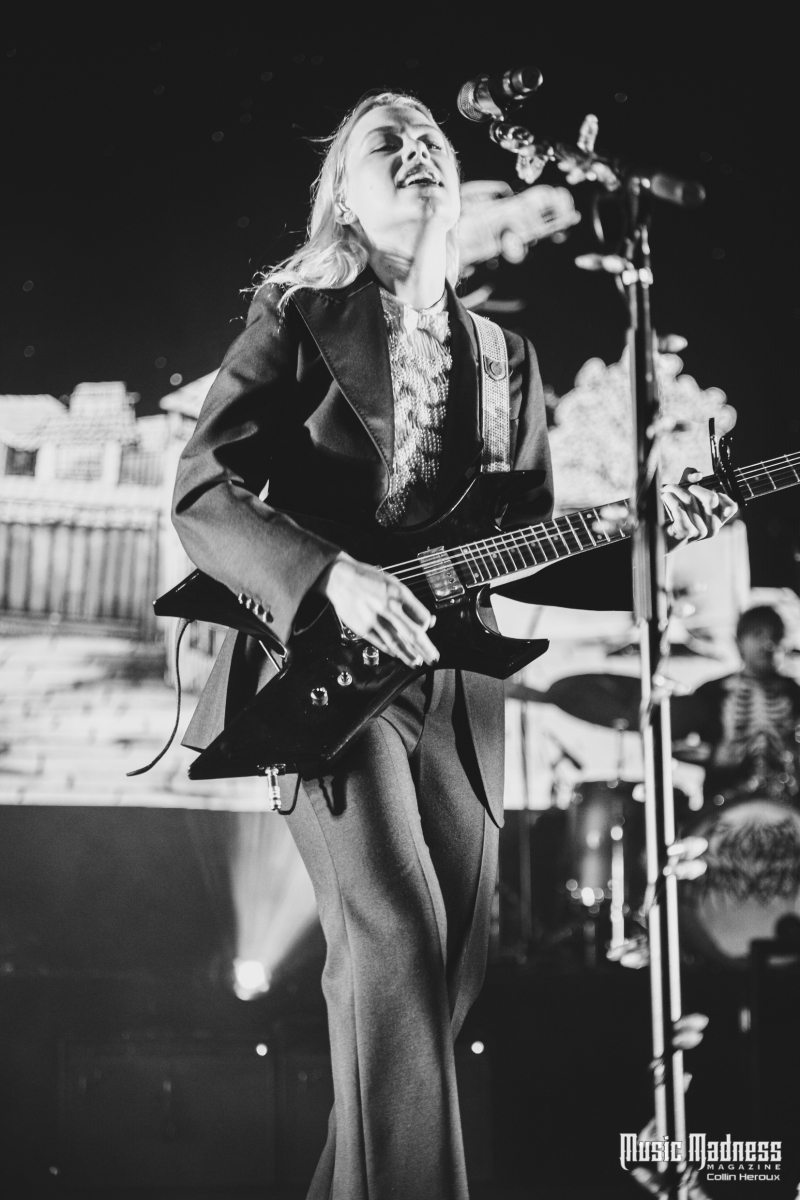

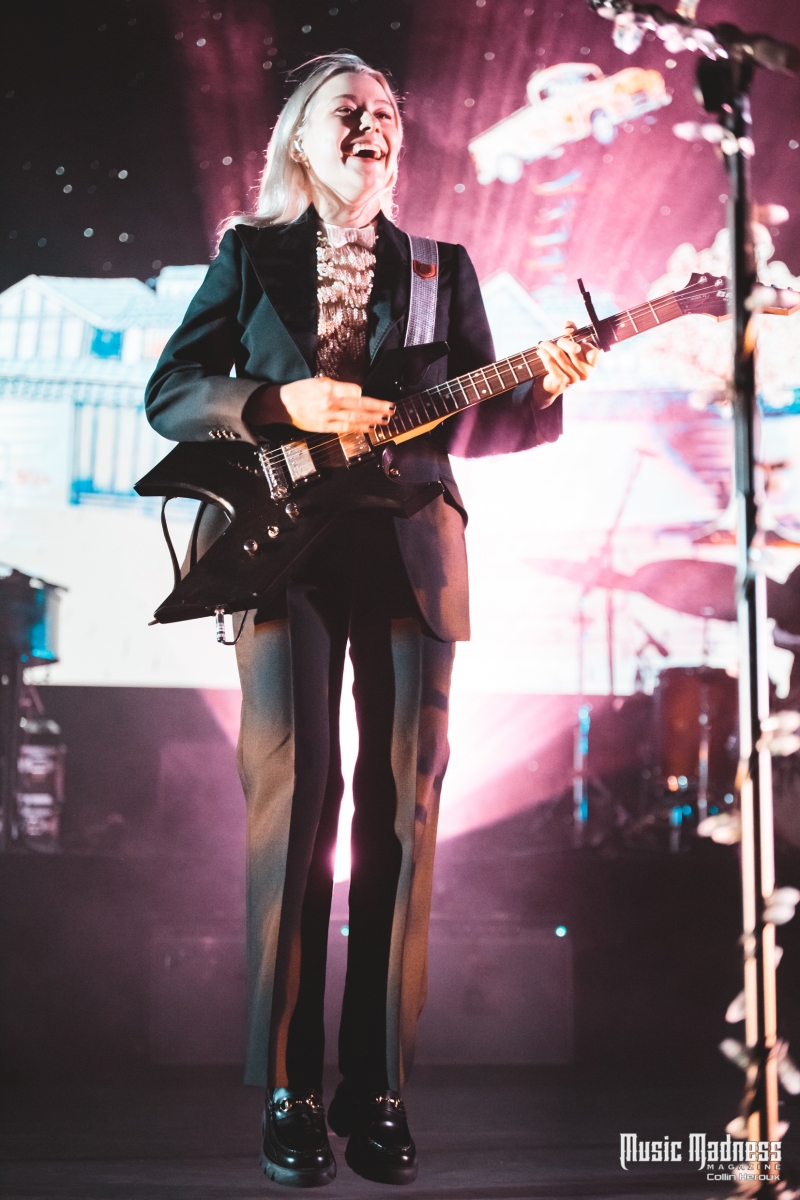

She elects to follow that with another standout single from Punisher, ‘Kyoto’. While it’s the most upbeat of any song therefrom, it’s also one of the hardest-hitting, where Bridgers confronts her father’s absence and a race between her conflicted resentment and his self-destructive behavior for who gets to him first. She dedicates the song to “everyone whose parents never went to a day of therapy for them”, a pang to the heart of the kid inside everyone in that audience who knows exactly what she’s singing about: the feeling of needing so much more than you got from a person who was meant to protect you but ended up adding to the problems you struggle with to this day. Pianist Nick White and keyboardist J.J. Kirkpatrick create the beautiful synth lines of the track while Bridgers switches from her acoustic to a sleek jet-black guitar. The five other band members are all wearing the skeleton suits that Bridgers dons on the album’s cover, though she is not wearing one this evening – she does remove her blazer to reveal a golden and pearlescent top that, viewed from a distance, perfectly imitates the symmetrical curves of a rib cage.

Throughout the night Bridgers offers glimpses between songs of what each is about, including joking that ‘Chinese Satellite’ is their “Coldplay song about how God doesn’t exist”, a likely reference to its big cinematic crescendo at the line where she most firmly denies the existence of a deity. But lyrically she takes no joy in looking up to the sky to see only manmade things, confessing she’d be an evangelical picketing on the corner if she could only believe it would let her avoid losing people in whatever comes next. Sartre famously wrote in his Essays in Aesthetics, “That God does not exist, I cannot deny; that my whole being cries out for God I cannot forget.” And, as all people do on some level, Bridgers confronts this conundrum herself with no easy answer – but that said, she does it in a musically fantastical fashion. Behind her, on the screen, a UFO careens over a city, and in the song’s closing verse a tractor beam emanates from it and picks up a little ghost figure from the foreground of the pop-up, a reference Bridgers herself and the cover of Stranger in the Alps, an impossible hope to return to a time before loss.

To cheers and whistles and screams at the end of each song, Bridgers takes some time to address the audience mid-show, saying, “It’s really cool to get that type of reaction out of like, some folk music,” although truthfully she’s underselling it a bit in that humility. There’s a kind of universality to her songs that so few writers access consistently, and a great deal of that owes to her preternatural ability to articulate the deepest recesses of sadness and parse them out through music, which on Punisher has only grown more lush, diverse, and ornate. Kirkpatrick provides a soaring trumpet solo on ‘Savior Complex’ drummer Marshall Vore comes out from behind the kit to play banjo on ‘Graceland Too’. Vore is a frequent figure in Bridgers’ songs, both in ‘Scott Street’ – which sees everyone in the audience hold up their phone flashlights ersatz lighters – and in ‘ICU’, which Bridgers says is about “arguing with your family about politics”, but whose scope extends beyond that, seemingly looking at a hard time in their friendship. “I don’t know what I want / until I fuck it up” she admits, in one verse capturing the essential whole of a universal human dilemma.

As the evening nears its close, Bridgers once again addresses everyone, thanking them for selling out the shows. “It’s been great after playing personal concerts for my dad for so long,” she confides and considering the lyrical content of ‘Kyoto’ that insight into what she’s been up to during the pandemic and her relationship with her father is interesting and hopeful. The final song of the night is, fittingly, ‘I Know the End’. Behind her, the storybook opens one last time to a house in disrepair down to its dilapidated white-picked fence, all of which catch fire as she sings the final rousing verse, driving through a pastiche of a uniquely American apocalypse. The song explodes in sound, Bridgers shreds her guitar alongside bandmate Harrison Whitford, Vore and bassist Emily Retsas create a pounding sonic backbone, and the night reaches its emotional apex, culminating in a scream shared between Bridgers and the entire audience, the very definition of catharsis.

Rather than try to top that moment with a traditional encore, Bridgers returns to the stage solo with an acoustic guitar for one last piece – a cover of Bo Burnham’s ‘That Funny Feeling’. The songwriter and comedian’s special, Inside, was a key fixture of the pandemic era, its surrealist humor not enough to disguise Burnham’s true-to-life descent into severe depression during perhaps the most isolating time in many a generation, all while creating some of the most stinging, iconic, humorous material he’s ever done. While Bridgers started writing a good deal of Punisher pre-pandemic, they’re kindred spirits in the sense that in a time of total despondency, they gave to the world beautiful works that didn’t turn from the sadness or loneliness, but confronted it, often with a desperate need. The band returns to the stage one by one and starts playing, growing the composition to one much larger than Burnham’s, while still preserving the fragility that he imbued in his original. Bathed in the light of a classic TV error screen, the song builds and then fades, the band waves goodnight, and in the soft orange glow that then shines on the audience, one can’t help but feel that they deeply needed that experience, whatever it may have meant from person to person. It wasn’t just a reunion of a band, it was a reunion of a band with their audience, audience with band, and for many, audience with self.