It is hard to believe that it’s been more than a year since the release of Idles’ astounding sophomore album, Joy as an Act of Resistance. The English band turned heads immediately in 2017 with their debut record, Brutalism, and since then have been riding an ever-upward wave of success, by virtually any metric. And they’re far from done — the five-piece band recently teased fans with updates on the recording of their third record, which looks to feature more piano, as well as an appearance by legendary violinist Warren Ellis of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

They’ve managed to do all this in between an extensive touring schedule, sandwiching a deluge of festival appearances across the UK in summer between two US tours, one in spring (which we covered), and their latest, which brought Idles to the sizable room at Boston’s Royale nightclub on a brisk mid-October evening, a queue of eager fans lining Tremont Street as far as the eye could see, nearly everyone wearing a shirt or a pin or a jacket adorned with the band’s eye-catching artwork or a turn of phrase from their online “AF Gang” community.

The band takes the stage just after 9pm and emerges in shadows. The first note to ring out is the menacing bass of Adam Devonshire, and with drummer Jon Beavis he forms the patient introduction to the first song of the night, ‘Colossus’. Dev’s one repeated note is enough to send shivers down the spine, as if one were listening to the heartbeat of some ancient and massive apex predator. Singer Joe Talbot stalks the stage and finally comes to plant his Doc Marten shoe squarely on the monitor wedge, gazing out into the crowd as he begins to sing the first line of the song. It’s his own personal origin compressed into a few minutes, growing up an outsider in a corner of the country where “nothing ever happens”, saddled with a club foot, and struggling with addiction for decades. As the song builds, guitarists Mark Bowen and Lee Kiernan enter gradually, flanking Talbot on either side of the stage, triggering a rise in the song’s pace that culminates in Talbot’s narration morphing into a scream, then falling into near-silence before exploding in a joyous second movement that serves as the perfect parallel to the band’s meteoric path into the zeitgeist.

Like every Idles show, the night is a communion, an affirmation in music that everyone in attendance is a part of something larger than themselves. “Fuck that fame bollocks. We are just as important as you,” Talbot declares, his very sentence structure implying that the audience are the ones who are important in the first place. This is a band that lives their credo on a daily basis, and Talbot makes his values unequivocally clear throughout the night: self-love, community, an end to toxic masculinity, and a political landscape that values human dignity over borders. Talbot praises Britain’s National Health Service at the start of ‘Divide & Conquer’, and in this heated American election season the thought of universal healthcare elicits almost immediately chants of “Bernie!” from within the crowd. Idles’ message is as resonant here as it is in their home country, with each nation seemingly perched on an existential precipice between fear and love, isolation and openness. And there’s no question where Idles stand on the matter.

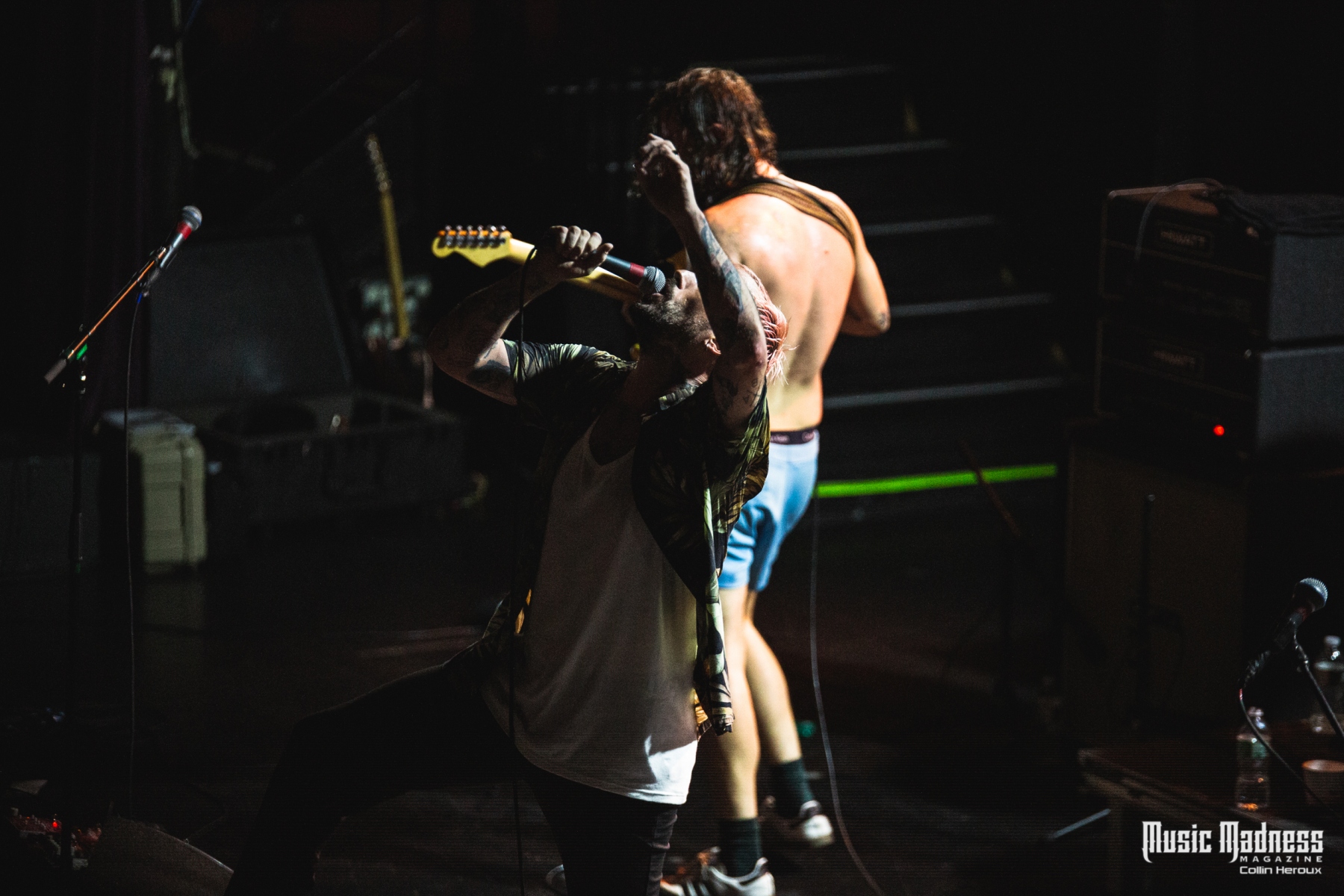

As the night goes on Bowen and Kiernan are out in the throng almost as much as they’re on stage, as if they feel a desire to engage with the audience as powerful as the audience’s desire to do so with them, refusing to let their instruments get in the way. They journey as far as the lengthy wires feeding into their guitars will allow, and Bowen even throws down his axe at one point as he’s hoisted on his back above the crowd, moving outwards into the throbbing pit of people as audience members are being carried in the opposite direction. Onstage, the two guitarists swing their headstocks in wild arcs toward the sky as they track the beating heart of the band just as much as the rhythm section.

With every song played coming from their two studio albums, the night was a perfect encapsulation of how the band has grown and changed in the mere year and a half between their first and second record. Forged in the dark depths of Talbot’s trauma, both Brutalism and Joy as an Act of Resistance take some of the most tragic moments of his life and turn them into anthems of resilience – but in different ways. The tracks from Brutalism show a band looking inward, harnessing their grief and rage to make songs documenting anger and depression, a snapshot of the world immediately around them in their native Bristol. ‘1049 Gotho’ tackles the topic of mental illness head-on, just as ‘Benzocaine’ does addiction; it’s music meant to speak to the raw hardship of bearing these burdens.

The tracks from Joy, by contrast, show a progression toward taking up the mantle of positive problem-solving, extolling the virtues of immigration in ‘Danny Nedelko’ and presenting a more analytical cross-section of sadness with ‘Samaritans’, the latter named for the UK’s suicide hotline where workers are staffed around-the-clock to lend an ear and a hand to those in crisis. It’s a treat to hear the band flit between these two phases seamlessly, and tantalizing to imagine how the band’s perspective might expand even further as they craft their third major release. Years from now, listeners may well reflect on the evolution of Idles as something akin to watching Radiohead evolve between The Bends, OK Computer, and Kid A – writing history in real-time.

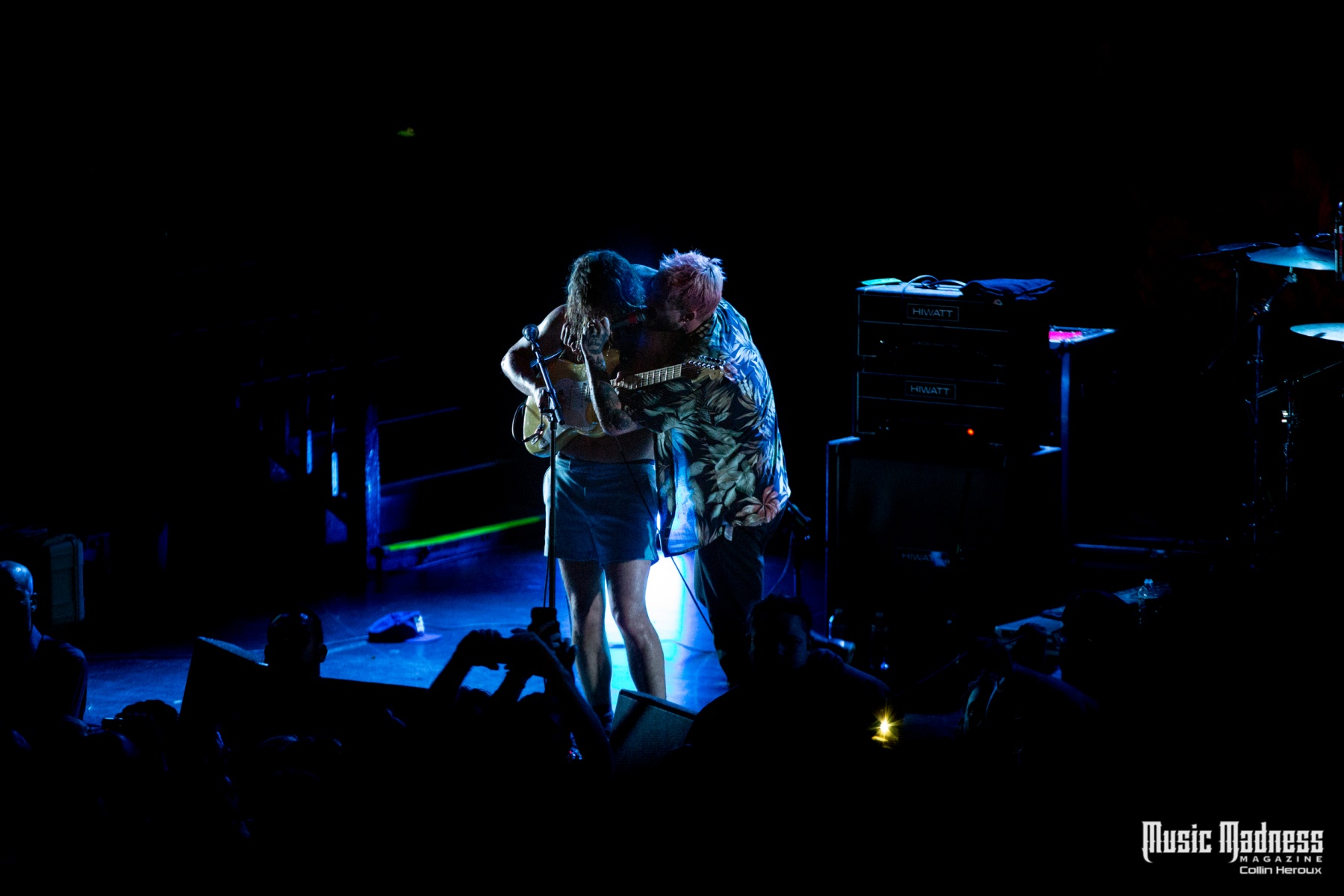

In a futile attempt to take something beautifully complex and condense it to a single sentiment, an Idles show might be said to be about harnessing the familial energy the band has and sending it out to a wider audience. One can see it in how the band members interact – the pairing of Bowen and Kiernan in their endless antics of playful one-upsmanship; the way Talbot hangs on Bowen as they both look out over the crowd; the way all of them jackknife up and down together in the final locked groove of ‘Rottweiler’ – these five are about as close and united in purpose as people can be. And when Talbot takes his microphone from his lips, leans his head back, Hawaiian shirt flagging, pink hair to the ceiling, and lets just the audience fill the air with the chorus of a song – it’s damn hard not to feel a part of that.

Review and photos by Collin Heroux