“WHY?”

This is the increasingly furious question repeated by Raygun Busch, singer of Chat Pile, in their song of the same name, one of the singles from their 2022 debut LP God’s Country. The full question is: “Why do people have to live outside?” And simply by the tone of his voice, you can know that there’s no answer that will be satisfactory, no explanation that will justify the level of human suffering encompassed in leaving people to brave the elements in a country with the resources and means to do otherwise. It’s a scornful, pugilistic interrogation.

The album’s title is pointed – and so is the band’s name. Apart from likely being quite confusing for French speakers, it refers to a waste byproduct of the mining industry in the heartland of America, lead-infused poisonous material really only seen in a handful of American states, including Chat Pile’s native Oklahoma. There it exists as its own geographic structures, hills fabricated of deadly gravel dotting the landscape. The worlds that the band visits in their songs are the perspectives they explore are equally ominous, a dense amalgam of dread stretching to every corner. A (suspiciously uncited) line on the Wikipedia page for chat reads: “Although poisonous, chat can be used to improve traction on snow-covered roads; as gravel; and as construction aggregate…”, those first two words tasked with an absurd amount of heavy lifting.

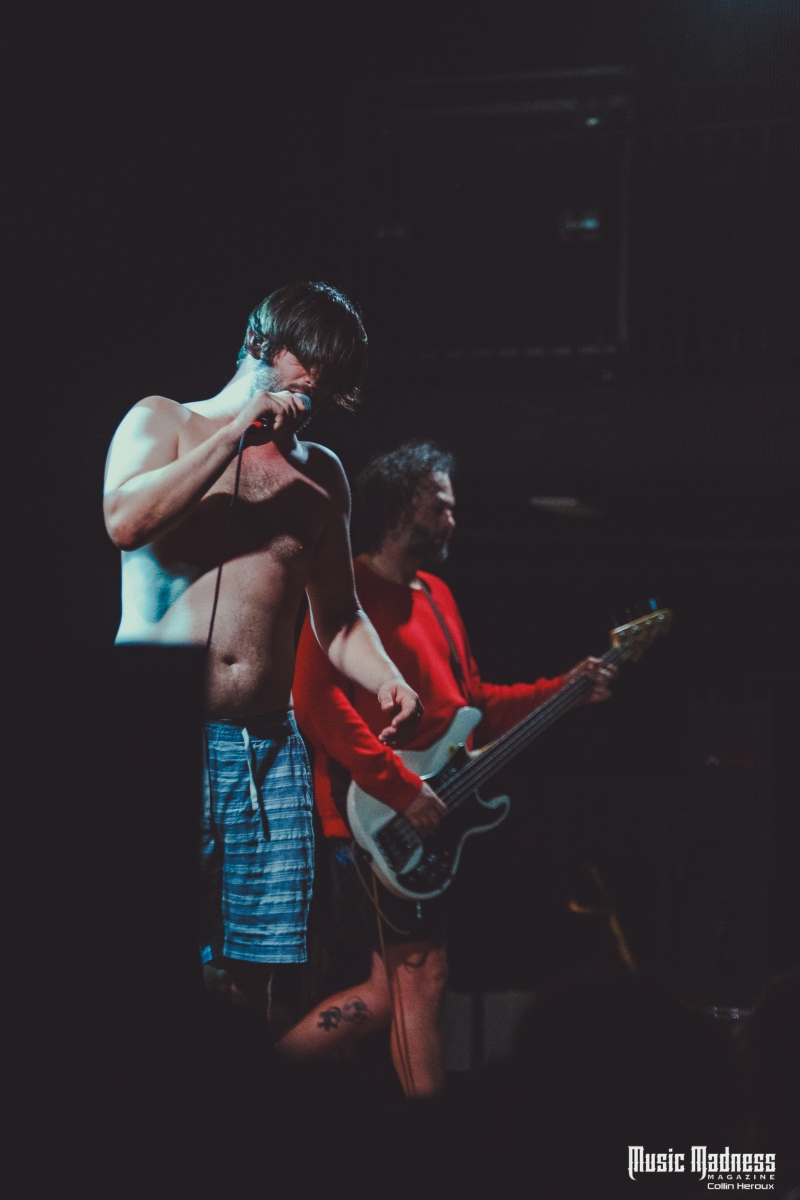

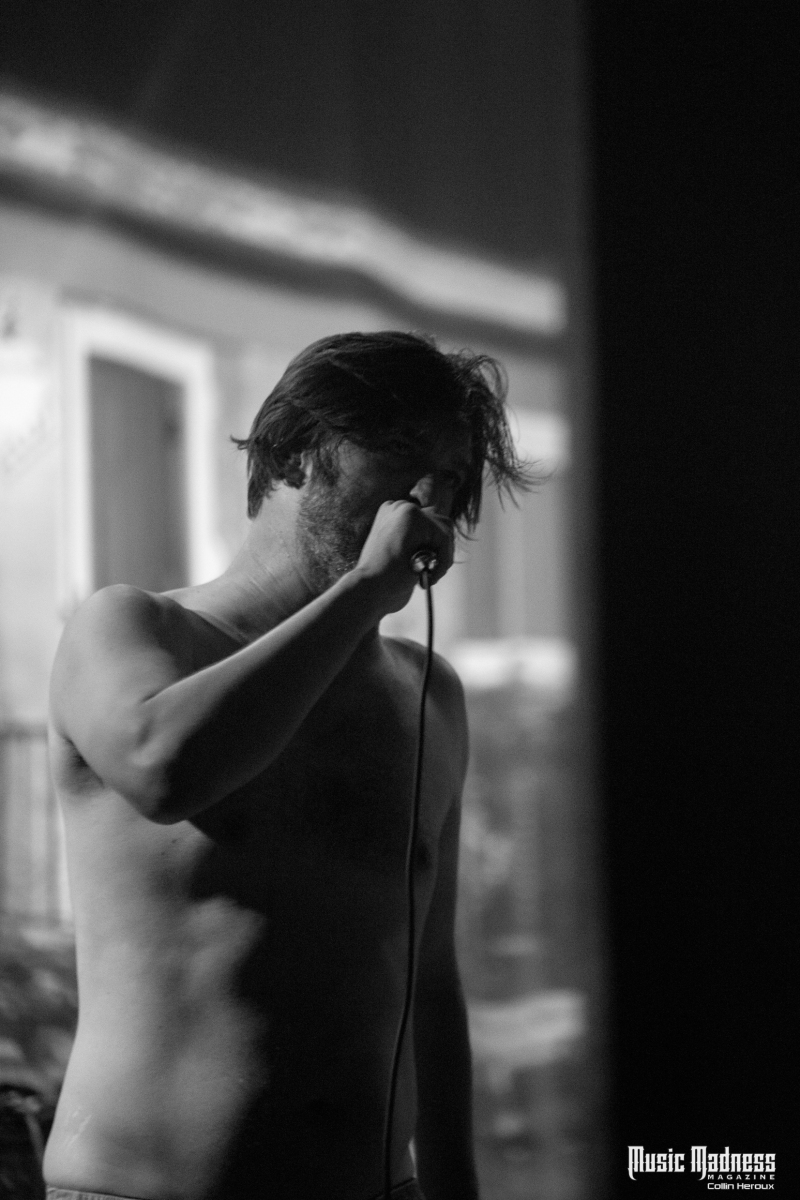

Chat Pile inspires incredible energy in their audience – their visit to Cambridge’s Sinclair Club is sold out and one of the most mobile, sweaty gigs in recent memory there, even on a Monday night. Their companions on the bill, Connecticut post-hardcore firebrands Intercourse, and fellow Midwestern titans Nerver inspire everyone to cut loose. It’s no surprise that a few songs into Chat Pile’s set, I feel a tapping on my head as I’m squinting through the viewfinder of my camera; someone’s crowd surfing to the edge of the stage and they’re looking for a bit of support, which they, fortunately, find on neighboring outstretched hands. By this point Busch has discarded his shirt somewhere, not to be seen for the rest of the set. Like each of the band’s four members, Busch performs under a pseudonym – there’s Cap’n Ron on drums, Luther Manhole wielding the guitar, rounded out by the mononymous Stin on bass. Busch is also quite fond of films, and between most songs, he has a little bit to say about movies he’s seen that remind him of Boston, alighting on an anecdote about skipping school to watch The Departed.

But apart from those interludes, Chat Pile has one mission: confronting the listener with the unbridled reality of their songs. Their nightmarish air sticks to your skin, barging its way to your eardrums, enveloping you; the added calamity of bodies crashing around from the circle in the middle of the room only accentuates it. This is the essence of it: brutality. Not cruelty, to be sure – people are still looking out for each other as is the unspoken edict of the pit. But while sometimes people mosh as a relief from outside forces, here they’re spinning around in the tempest with them. Chat Pile offers an uncompromisingly dark look into scenes and characters – the institutional failure explored in ‘Why’ is but the tip of the iceberg.

Chat Pile’s output is sometimes referred to as sludge metal, and you can hear why with the rugged undulations that form most of the music. But other close relations are noisy no-wave predecessors such as early Swans. Busch is intentionally sparing with his lyrics, vocalizing only enough to get to the heart of the matter. In ‘Slaughterhouse’ he repeats, “You never forget their eyes”, a sentiment that in five words is unambiguous: the sensation of looking into the soul of an innocent creature moments before its life is snuffed out, the culmination of a short existence full of dread and failure to comprehend the wretched, unfeeling machinery around it. Chat Pile’s music takes them to the perspective of killers of all stripes: sometimes the cattle are literal, sometimes metaphorical (here’s looking at you, Arby’s). There are moments of “relief”, if you can call it that; ‘Pamela’ spins Busch’s affinity for film into music, taking the perspective of horror icon Jason Voorhees’ mother, and at the very least flickering briefly from fact into fiction though tonally things remain similar. But the departure is fleeting, and that’s the point – when you live a “haunted life”, there’s only so much looking away one can do.