“This wall was built years ago, to the Protestants on this side fightin’ with the Catholics on the other… It’s there twenty-four hours a day, but thing is that – it divides two communities, but every Saturday night, hundreds of people go out downtown, just go out clubbin’ – forget about the divides between each other.”

This interview sample, taken from Desmond Bell’s Dancing on Narrow Ground: Youth & Dance in Ulster, serves as the introduction to ‘Parful’, one of the most firmly club-oriented tracks on their latest album, Fine Art. For the uninitiated, the structure in question is a so-called “peace wall” – edifices built across Northern Ireland, chiefly in its capital Belfast, to minimize sectarian violence during the thirty-year conflict known as “the Troubles” in the region. So hard was the divide that, to this day, ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’ are used as interchangeable terms with ‘unionist’ and ‘republican’, respectively – the former support Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK, while the latter hope for it to break away and form a complete Republic of Ireland. Moreso than any other point on the album, this opening bit of ‘Parful’ highlights the intersection of political division and universal enjoyment that marks where Kneecap’s music exists.

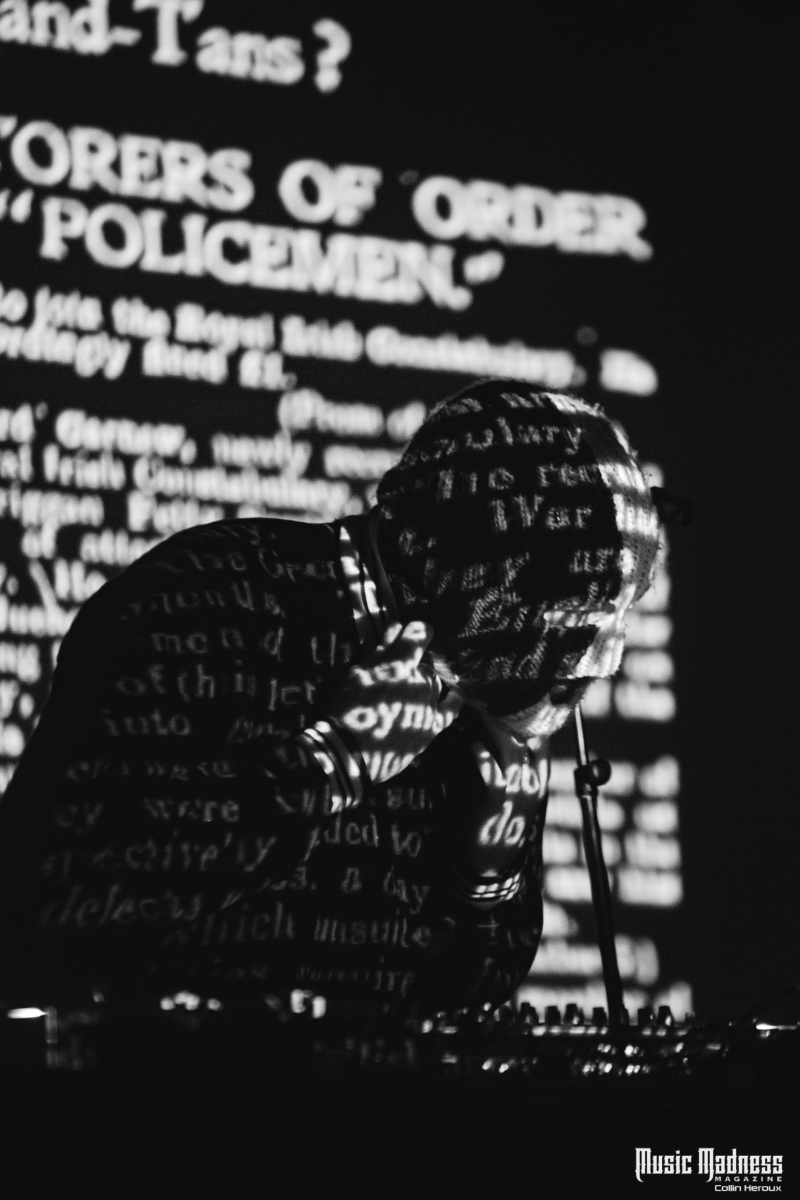

On the back of a film that shares the band’s name – and includes appearances from the likes of Michael Fassbender – the trio of Mo Chara, Móglaí Bap, and the masked DJ Próvaí have established a hugely successful career in hip-hop, complete with their own iconography. A black-and-white render of Próvaí’s mask adorns the cover of Fine Art, centered in a picture frame, and throughout their show at Boston’s Paradise Rock Club, they project various cartoon caricatures of themselves behind Próvaí’s station at the decks. While it may not surprise that Kneecap have sold out a venue in Boston, given the city’s ties to Irish heritage, their US run has been doing so all over the country. That likely owes as much to the band’s subject matter as it does rising sympathies for Sinn Féin, the leftist Irish-republican party which recently became the dominant force in Northern Irish politics; ultimately, Kneecap are about bringing people together for a good time, reveling in the kind of camaraderie and excess that can only serve to unify. (That said, the chant at the end of ‘Fenian Cunts’ gets a full-on chorus going among the Boston crowd).

During ‘Your Sniffer Dogs Are Shite’, Móglaí Bap leans over the edge of the stage, one foot on the barrier, leaning into the crowd. A bit later Mo Chara shouts, “I need more!” out to the crowd, and throughout the night they tease with some far lower-stakes regional politics, comparing the crowd to that of New York the previous night to try to froth the room into even more of a frenzy. Things really seem to uncork around the time of ‘I bhFiacha Linne’, a tale from the point of view of some ruthless drug dealers collecting on a debt. The Kneecap name itself is the first winking joke of all the band made, as the behavior they often describe would be liable to get them kneecapped by hard-line unionists and republicans alike. But the music has the entire room undulating back and forth; some in the crowd have come in tricolor ski masks, in the style of DJ Próvaíl; later, a guy in a leather jacket appears, hoisted on the shoulders of others, holding a big Irish flag in both hands.

A defining feature of Kneecap’s music is how it weaves seamlessly between English and Irish. The Irish language – which Americans generally learn to refer to as Gaelic – is one of many facets of Irish identity that the English attempted to suppress as part of their dominion over the territory. It wasn’t until 2022 that an act was passed recognizing Irish as an official language of Northern Ireland. Despite the end of the Troubles and various reconciliation measures, the roots of the division run deep in Northern Ireland. But do you know what helps ease that division, alongside the wall-shaking beats of a club or the cheerful din of a pub? Drugs. And Kneecap advocates a certain sort of better coexistence through chemistry.

‘3CAG’ – the title of their first release as well as the opening track of both Fine Art and their Boston set – is an acronym that translates to “3 consonants and a vowel” – MDMA. ‘I’m Flush’ is a certified club classic to bump on any given payday, and they play it into ‘Rhino Ket’, which is about exactly what it says on the tin. The flipside of excess is acknowledged too, particularly on the song ‘Better Way to Live’, which pipes in a chorus from Grian Chatten of Fontaines D.C., singing about finding slivers of joy in stretches where drinking has become routine.

Disappearing backstage while ‘Parful’ plays over the PA, serving as a kind of encore break, DJ Próvaí reappears having changed his mask from the Irish flag to a Palestinian one. The parallels are obvious: two populations living separated by walls, social castes dividing them; one entity backed by vast military power, the other not so much. The desire for self-determination in both places long predates the birth of any member of Kneecap, and goes back many generations before that. The British had a hand in both conflicts, naturally – so it’s fitting that the encore begins with “Get Your Brits Out”, but even then it’s a classic Kneecap subversion of expectations. The song is actually a fanciful tale where Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap take an entourage of unionist political figures out for a night of utter debauchery. And while sectarian divides at the highest level may never be mended by a night out popping ecstasy and who-knows-what else with aging politicians, it’s certainly a fun enough gag to base a song around. In the end, Kneecap are more than happy to refer to themselves as a group of hoodlums; but that kind of unassuming attitude might end up being a truly formative power for the youngest generations of Northern Ireland – or anywhere else that enjoys a bit of the craic.

Photos and words by Collin Heroux